THE DEATH OF SOCRATES

- Seda DOGAN DEMIREL

- Jul 27, 2025

- 6 min read

Date: 1787

Artist: Jacques‑Louis David

Art Movement/Period: Neoclassicism

The Death of Socrates is one of the most influential paintings of the Neoclassical era. In the 1780s the French artist Jacques‑Louis David turned toward classical subjects and austere aesthetics; he completed this canvas in 1787 and exhibited it the same year at the Paris Salon.

Paris Salon, the prestigious annual show organized by the Académie des Beaux‑Arts. The Academy embraced a traditional approach to art. Paintings that portrayed historical, mythological, and allegorical scenes with realistic detail were favored, which helped make David popular. Today the painting is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

A Cup of Hemlock & Boundless Courage

The Greek philosopher Socrates (469–399 BC), a pioneer of Western philosophy, was sentenced to death in 399 BC for allegedly leading young people to think critically and for showing disrespect toward the traditional gods. This painting captures the moment he ends his life. Socrates must either renounce his beliefs or drink a cup of hemlock poison, and he chooses death.

Painting Socrates’ death became a very popular theme in art. The philosopher’s name lived on because of how he responded to his trial, and for that reason his execution was viewed as a socially and politically unusual event.

Socrates sits upright on his bed. With one hand he reaches for the cup of poison, and with the other he points to the sky. This gesture shows his belief in the immortality of the soul and his strong attitude toward death. Even in his final moments, he continues to teach his students.

For Socrates, death is part of his teaching, a release of the soul from the body. His calm reach toward the cup shows that he accepts his fate peacefully.

Plato writes that after thanking the Greek god of health for a peaceful death, Socrates “raised the cup to his lips and drank cheerfully and quietly.”

David presents this harrowing picture in an extremely readable way.

From Chains to Freedom...

Open metal shackles lie on the stone floor. The redness on Socrates’ wrist shows that he has just been released from them. This detail represents his physical pain. On the bed we see a lyre, which is a nod to poetry, music, and art.

Why Are There Twelve Other Figures?

Despite Socrates’ firm stance, he is surrounded by students and friends who are overcome with deep sadness and distress.

Around him there are twelve people—apart from Socrates himself. This number is a deliberate reference to Jesus’ twelve Apostles and gives Socrates a sort of sacred meaning.

The bearded man holding Socrates’ knee is his close friend Crito. He seems to beg Socrates to think again: placing his right hand on the philosopher’s knee to interrupt him, while lifting his left hand toward his own face as he waits for an answer to the escape plan. This gesture shows Crito’s loyalty and his helpless fear of losing his friend. Socrates, however, is determined to refuse the offer. Painter Jacques‑Louis David underlines the weight of Crito’s plea by signing his name clearly on the base of Crito’s seat.

Immediately to Socrates' left and behind him, listening with curiosity, are two young men: Simmias and Cebes. Both of them appear in Plato's Phaedo dialogue, discussing immortality with Socrates.

The young attendant who hands Socrates the hemlock turns his head away and covers his face with one hand. This posture shows the heavy emotions that come with witnessing Socrates’ death; he cannot bear to face the reality.

The person weeping in the background, leaning against the door arch, is Apollodorus. According to the story, he is asked to leave the room because of the extent of his grief.

Why Does Plato Look Old?

The old man sitting at the foot of the bed, his head bowed, is Plato, Socrates’ student. In real life Plato was younger than Socrates, but here the artist shows him as an elderly sage. David does this on purpose to stress Plato’s wisdom.

Near Plato’s feet lie a scroll, an ink pot, and a pen. David has placed his initials on the stone block that holds the scrolls.

Jacques‑Louis Davids Hidden Symbols

The lyre is unusual in a prison, but it refers to Plato’s dialogue Phaedo, where Socrates and his students discuss whether music can explain the link between body and soul.

David studied the text deeply, and this is clear in his painting.

Time Flows on the Stairs

In the background, Socrates’ wife Xanthippe is climbing the stairs and turns back for one last look. This glance shows the sadness of Socrates’ family at this tragic moment.

The figures moving upward on the stairs make the viewer feel that time is passing: Socrates has already said goodbye to his family, and while he drinks the hemlock another farewell with his followers is about to happen.

The careful details in the painting clearly show that David had studied Plato’s Phaedo, the dialogue where the Greek philosopher discusses the immortality of the soul.

David: “In art, how an idea is shown and expressed is much more important than the idea itself.”

Is This Painting a Manifesto?

In this work David praises the values of ancient Greek philosophy, but he also points to the political mood of his own time. He is inspired by revolutionary ideas, and his paintings carry clear political messages. A friend of Robespierre, he paints on the eve of the French Revolution, and the story of Socrates becomes a call to revolt.

Socrates’ decision to die for his beliefs stands for resistance against unjust authority just before the Revolution. The painting’s simple yet powerful design leaves a strong impression on the viewer.

In the years after the picture was finished, the French monarchy fell and the First Republic was created. During this period both the painting’s patron and, later, David himself were put in prison.

The patron of the painting was Charles‑Louis Trudaine de Montigny, a young member of the Paris parliament and son of a finance minister. During the one‑year Reign of Terror led by Maximilien Robespierre and the Jacobins, Trudaine was jailed and then executed by guillotine on 26 July 1794. Although Trudaine asked David for help, the artist—who by then was working with the revolutionary government—did not answer his plea.

What MA‑XRF Reveals: Erased Secrets

MA‑XRF scans show that there was originally an oculus window in the wall behind Socrates. David later covered the window to give the scene a harsher look and painted a ring and hook in its place.

The same analysis also detected extra figures on the stairs: apparently a cloaked woman carrying a child. Their identities are not certain, but they may be Socrates’ wife Xanthippe and their youngest son. David later painted over these figures.

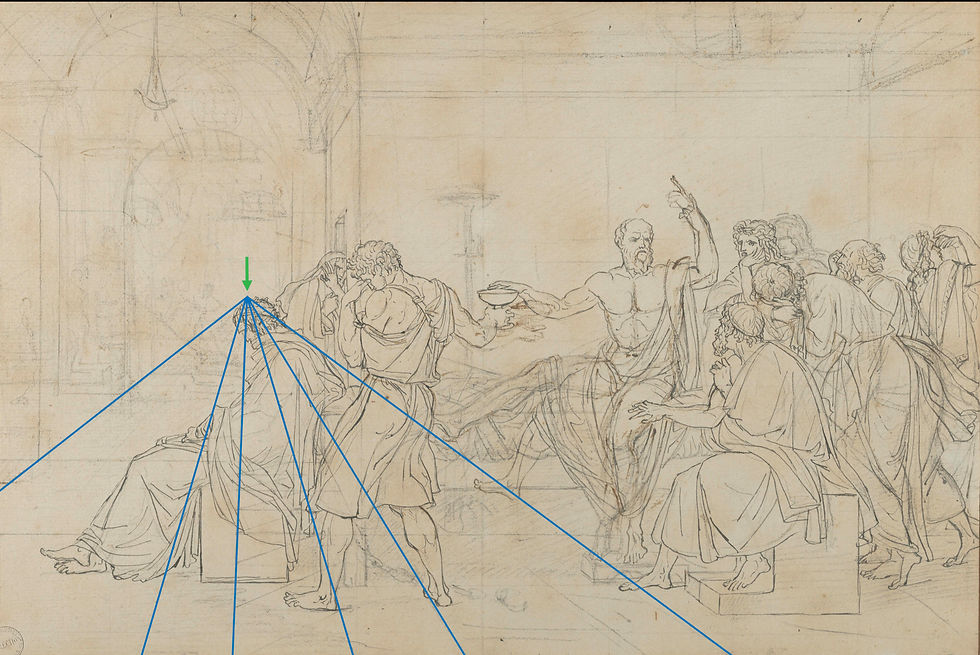

The Architectural Layout: The Key of One‑Point Perspective

The background uses a one‑point perspective, creating a clear and logical space. We see a barrel‑vaulted ceiling with arches—rare in ancient Greece but common in ancient Rome. The vanishing point sits just above Plato’s head, so the viewer’s eye naturally focuses on him.

X‑ray images show a tiny pinhole at that vanishing point where hidden guide lines meet. Most pentimenti—visible traces of the artist’s earlier ideas—gather around Socrates and the young cup‑bearer.

The Language of Light: Deep Reds and Cool Blues

David pays special attention to colour. The reds at the edges of the painting are pale, but they grow into a strong, dense red toward the centre. The whitish‑blue shades in Socrates’ and Plato’s robes highlight their calm nature and wisdom. These colours simplify the scene and keep the viewer’s focus on Socrates’ courage and determination. Like artists in ancient Greece, David also takes great care with the figures’ anatomy.

Prison and freedom are two key themes in David’s art. He shows that survival is less important than loyalty to high ideals. With this painting he presents not only an execution but also the greatness of human will.

References:

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Vasileios Zagkotas and Ioannis Fykaris, "Approaching the ‘Death of Socrates’ through art education. A teaching proposal and the introduction of a new typology for teaching with similar artworks"

Wikipedia, "The Death of Socrates"

Perrin Stein, "Prisons Real and Imagine" Metropolitan Museum of Art

Charlotte Hale and Silvia A. Centeno, "The Death of Socrates New Discoveries - Metropolitan Museum of Art"

Dr. Bert Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Jacques-Louis David The Death of Socrates"

Kelly Richman-Abdou, "How David's 'Death of Socrates' Perfectly Captures the Spirit of Neoclassical Painting"

Wikipedia, "Phaidon"

Comments