GINEVRA DE'BENCI

- Seda DOGAN DEMIREL

- Jul 18, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 23, 2025

Date: 1474/1478

Artist: Leonardo da Vinci — Late phase of the Early Renaissance

One of Leonardo’s earliest oil paintings and one of his few surviving works without a religious theme. At first glance the image can look austere, almost plain—until you spot those unmistakable Leonardo touches.

“The first intention of the painter is to make a flat surface appear as a modeled body emerging from the plane; whoever excels in this deserves the highest praise. This crowning skill is born of light and shade—chiaroscuro.” — Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci is one of his early attempts in exactly that direction.

The Life of Ginevra de’ Benci

Ginevra de’ Benci was the daughter of a leading Florentine banker; she was born in August 1457 at a villa near Florence. The Benci were allies of the Medici and nearly matched them in wealth.

In early 1474, at sixteen, Ginevra married Luigi Niccolini, age thirty-two and recently widowed (about six months). The Niccolini were a respected Medici-aligned family that had held civic offices in Florence for generations. Luigi served as gonfaloniere (chief magistrate) in 1478 and as one of the six priore governing Florence in 1480; his three brothers also held significant state posts.

Despite their standing, the Niccolini finances were strained. In the 1480 tax return Luigi declared he had “more debt than property.” Ginevra’s fragile health was cited among the causes of the family’s decline. Delicate yet lovely, she was frequently under a doctor’s care. The couple had no children. Because of her small frame she was nicknamed “La Bencina” (“little Benci”). Deeply devout, she collected religious objects, enjoyed music, and wrote poetry.

The Benci Family

Artistic interests ran in the Benci household. Ginevra’s grandfather Giovanni d’Amerigo Benci—a wealthy and charitable merchant with eight legitimate and two illegitimate children—founded the Suore Murate (enclosed nuns) convent and commissioned three altarpieces from Fra Filippo Lippi. Her father Amerigo served on Florence’s ruling body, the Signoria, in 1462 and 1467; he attended meetings of the Platonic Academy and presented the philosopher Marsilio Ficino with a precious manuscript of Plato.

Who Commissioned the Painting?

One view holds that Leonardo received the commission around Ginevra’s 1474 marriage, likely through the assistance of her father. Leonardo’s own father, Piero da Vinci, provided notarial services to the Benci family on numerous occasions, and Leonardo is said to have been on friendly terms with Ginevra’s older brother.

Yet the portrait does not behave like a conventional marriage or betrothal likeness. Instead of the standard strict profile used in patrician bridal portraits, Ginevra appears in three-quarter view. Rather than the lavish jewels and richly embroidered finery typical of elite wedding imagery, she wears an extremely plain brown gown. The black wrap at her shoulders would be an odd accessory for a wedding celebration.

Another hypothesis: the painting was commissioned not by the family but by Bernardo Bembo, Venetian ambassador to Florence in early 1475. Then forty-two, Bembo already had a wife and a mistress, yet he conducted—openly, and in all likelihood chastely—a close relationship with Ginevra. Whether purely platonic or edging toward forbidden love has been debated; in any case a deep attachment grew between them, the kind that inspired poems in the Medici circle. The Florentine humanist Cristoforo Landino praised the bond: “Bembo burns with love; Ginevra holds the chief place in his heart.”

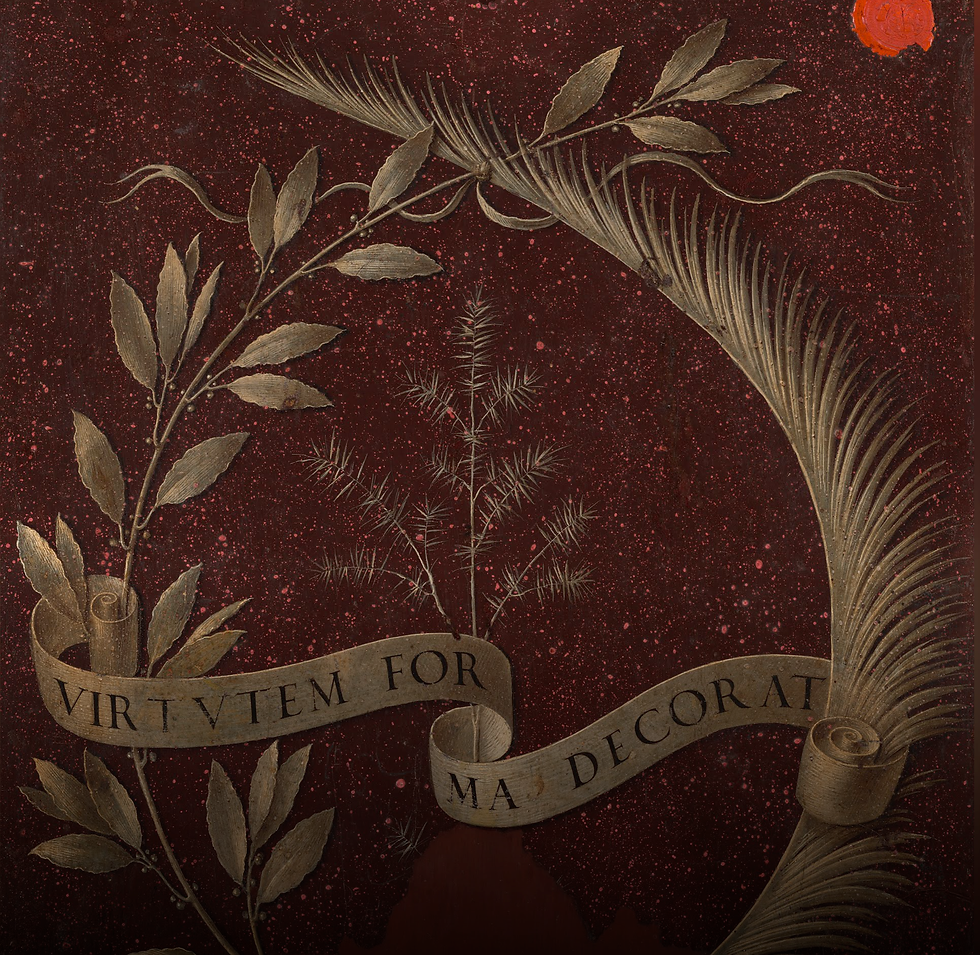

Leonardo painted the reverse of the panel with Bernardo Bembo’s emblem: a wreath of laurel and palm. Few visitors even realize the portrait is double‑sided. While the front records Ginevra’s outward appearance, the back hints at her inner character. Laurel and palm stand for intellectual and moral virtue; they encircle a sprig of juniper. In Italian juniper is ginepro—a clever play on Ginevra that also alludes to chastity. A scroll threads through the foliage bearing the motto “Beauty Adorns Virtue.” Infrared analysis shows an earlier layer reading “Virtue and Honor,” Bembo’s own device—evidence that bolsters the theory he commissioned the painting.

A Forerunner of the Mona Lisa

In this painting Leonardo experimented with new techniques and new poses. Working in exquisitely thin oil glazes, he captured the subtle modeling of Ginevra’s face and the hazy distance of the landscape with striking realism. Bathed in diffused light, she appears pale and melancholic—an impression that seems to reach deeper than the physical ailments her husband once reported.

Roughly the lower third of the original panel was cut away (certainly before 1780), which is why her hands are missing. A study of hands by Leonardo in the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, is often cited as a preparatory drawing for the portrait and helps modern scholars visualize the lost portion. The reconstruction shows how Leonardo broke from the older Florentine convention of bust-length profile portraits of women to achieve an innovative half-length composition. About 1 cm is also missing along the panel’s right edge. Aside from these losses—and some abrasion near the sitter’s nose—the painting is in remarkably good condition for its date.

Women Indoors… Until Leonardo

In the 16th century (and in much late-15th imagery) women were typically shown indoors, the outside world glimpsed only through a distant window. Leonardo, as he would again with the Mona Lisa, places Ginevra outdoors, beyond the threshold of domestic space.Why? To challenge social constraints on women? Or because he wanted to explore landscape?

Leonardo laid down smoky, feathered transitions—sometimes even blending with his fingertips—to avoid hard contour edges. You can see fingerprint traces: one just to the right of Ginevra’s chin where her curls meet the juniper against the sky, and another just behind her right shoulder.

What Is Ginevra’s Expression Really Saying?

Perhaps the most compelling feature is Ginevra’s gaze. Carefully worked eyelids intensify the air of melancholy that hangs over her. At first she seems to look down and left in thought; but study each eye separately and she begins to meet your gaze. Her eyes also hold tiny specular highlights—small spots of light from the sun striking the moist surface—that give them a liquid sparkle. Similar pinpoints catch on the curls of her hair.

This “spark of light” is a Leonardo hallmark. As he observed, a specular highlight remains white—unmixed with local color—and appears to move as the viewer moves. Imagine walking around Ginevra; those glints in her eyes and locks would seem to shift, “appearing in different places as each viewpoint changes.”

Spend time with Ginevra de’ Benci and the face that first seems blank gradually gathers emotional resonance. Is she lost in thought about her marriage? Bembo’s devotion? Or more private sorrows? Her life held hardships: chronic illness, no children, and yet an intense inner life—she wrote poetry.

One fragment attributed to her:

One fragment attributed to her: “Forgive me; I am a mountain tigress.”

In painting Ginevra, Leonardo probed the hidden life of the sitter and created an early psychological portrait—a line of inquiry that would become one of his most important artistic innovations. This work set him on the path that, some thirty years later, would culminate in history’s most celebrated psychological portrait: the Mona Lisa.

The faint, almost unreadable curl at the corner of Ginevra’s mouth hints toward that later, unforgettable smile. Ginevra de’ Benci is not the Mona Lisa—but she is unmistakably by the hand that would paint it.

References:

National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC) — Object entry & technical notes.

Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo’s “Ginevra de’ Benci” and Renaissance Portraits of Women (NGA Washington).

Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci.

The New Yorker Archives (selected essays referencing the painting).

Sara Jacomien van Dijk, “‘Beauty Adorns Virtue’: Dress in Portraits of Women by Leonardo da Vinci.”

Antony Molho, The Brancacci Chapel (contextual Medici Florence studies).

Comments